Becoming an astronaut was my biggest childhood dream. Who wrote it for me?

Like most kids, I wanted to be an astronaut. To compensate for geographical distance to Cape Canaveral (I grew up in a small town in Germany), my best friend and I designed Apollo mission shirts, erected a replica of 2001’s famous monolith on our front lawn, transformed our door bell into a Hal 9000 front panel, and built a space observatory on the roof of our house.

Most people look at NASA as a space agency and at my childhood projects as natural activities. However, NASA is probably one of the most successful marketing agencies in the 20th century and my childhood evidence of its enduring influence on society and individual biographies. Long before Steve Jobs did his meticulously planned product launches, Nasa managed to enrol millions of people into one of the biggest science education projects known to men. And whereas Steve Jobs would get hung up on tiny little iPhones, NASA had a really bold innovation in stock: the Moon.

So how did NASA market the Moon? David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek provide some fascinating clues in their book Marketing the Moon (2014). In the following, I add some of my own thoughts to offer a four-step model (based on an analysis of the rise of Botox Cosmetic).

Problematization

First of all, marketing the Moon required a larger political imperative. If the Moon was to be a solution to strive for collectively, as a nation, what on Earth was the problem? The Moon, a piece of rock, would have to be made an obligatory passage point in winning a more existential struggle between forces of good and evil – or the free world and communism. In cases where innovators have created a solution that is looking for a problem, marketers call this strategy problematization – defining a problem that has the potential to advance the focal actor’s economic or political goals.

Interessement

Just claiming that the Moon as an object of political interest was not enough, however. The Moon had to also be made an object of scientific interest. Unfortunately, most scientists before 1961 regarded the Moon as a pretty trivial object. Now NASA had to persuade them, through grants and scholarships, to redirect their research interests and agendas away from whatever they were working on and instead embrace the Moon. Likewise, citizens needed to be made to fall in love with rocket science, physics, astronomy, geology, and engineering. These disciplines could not only lend legitimacy to the project far beyond the political level. They also helped raise interest for other critical non-human actors such as the space suit, the oxygen tank, or the Moon rock.

Enrollment

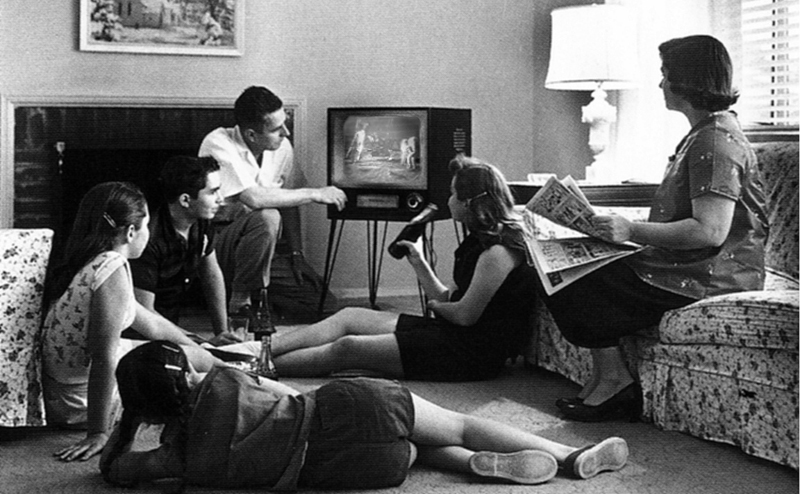

To recap, situating the Moon within a larger political struggle and making the quest a science project had given new meanings to the Moon, to Western democracy, science, technology, and the nation as a whole. But in order to captivate regular people, more work had to be done. The Moon had to be pushed into the American living room. Sociologically speaking, the emerging assemblage had to be translated into the everyday, and the media was the key to accomplishing this goal. Along these lines, NASA created a host of PR materials, fully-produced radio newscasts, interview reels, and brochures. PR people began to downplay rocket scientist Wernher von Braun’s dark Nazi past and instead played him up as a grandfatherly storyteller. The astronauts, their wives, their children, and even their pets were enlisted as media personalities, bringing the Moon ever closer to the American people. These personalities not only gave the Moon a human face. They also translated the complexity of a Moon mission into an easily consumable way of being American: creative, curious, scientific, hard-working, and boldly reaching for the stars. Marketers call this strategy enrollment – creating a network of representatives that translate the focal product into concrete, everyday social roles.

Mobilization

Lastly, citizens had to take their ascribed roles. For most of them, it meant turning on the TV at the right time and watching the action unfold. For me and millions of other kids born after 1961, it meant taking their seats at night on the roof of their parents’ house to watch the Moon with their telescopes. For most of my life, I looked at these events as moments of freedom and autonomy. It took me a while to realize that this was exactly the place where Marketing Mission Control wanted me to be.

So what has NASA really done? Putting a man on the Moon is certainly impressive. But the real accomplishment took place here on Earth. NASA has reshaped politics, science, technology, America, the family, and my childhood. It has created an enormous amount of new meanings, styles, associations, and fantasy worlds that live on in Daft Punk videos, Hollywood movies, and Elon Musk’s rocket engineering projects.

From a more critical perspective, however, it has also created several generations of citizens with a serious Moon fetish – folks who looked to the Moon and the stars, thereby neglecting to look at each other.

Further Readings

Robin Canniford’s book review for “Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Lunar Program” in Consumption, Markets, and Culture.